I recently completed a unit of Clinical Pastoral Education (CPE), at the Veteran’s Administration Hospital here in Pittsburgh. During my time at the VA facility, I visited patients in various life and medical conditions, met some amazing people, and learned a great deal about myself and my ministry. Early in my time there, I met a Vietnam veteran. The visit shaped my entire time in CPE and, in one way has brought me close to the end of a road in my life.

First, I need to share with you the landmarks I have passed on this particular path. When I was 10 years old, my oldest brother, Jon, was my hero and, next to my father, my most important role model. He went to fight in Vietnam. It was 1968, the worst year of the war. The television news bombarded us nightly with images of death, reports of opposition to our involvement, and editorials questioning our core goals as a nation and as a people.

I saw and heard these reports. But, all I cared about was that Jon would come home safely. I did not care about falling dominoes. I did not care about the welfare of people halfway around the world. I wanted our armed forces to bomb our enemy into oblivion so that Jon, my brother, would not be harmed.

Jon finished his tour of duty and returned home. We celebrated in our dining room the night he got back. There he was, thinner and a little older, but still the brother I knew and loved. Almost the next day, however, the change started. Jon talked less and spent much more time alone. He stayed up all hours of the night, reading voraciously. He and his wife quarreled more often. Jon’s patience with his children grew shorter. I did not know what was happening, but sensed that some part of my brother was missing.

I entered junior high school and began a lifelong passion for history, particularly about Nazi Germany. I, too, read voraciously. One book, titled Treblinka, chronicled the events that occurred at the concentration camp of that name in Poland. The account introduced me to the Holocaust and engaged my curiosity and revulsion about the potential for humans to harm each other. My interest in that era of our past gradually shifted away from battles and military strategy, to the people of Germany…not the soldiers and fanatics, but nurses, store owners, professors, and ministers…everyday people. I still believed in war, at least that we needed to fight wars to protect ourselves, our way of life, and our basic principles of freedom and democracy.

One thing that did die in me during that time was my belief in God. Like many people who travel the path that leads to atheism, I could not imagine how the God that all of my friends believed in could ever allow a thing like the Holocaust to happen. Why would the father of Jesus condone war at all? As a result, I lived unchurched for many years, until I happened to discover Unitarian Universalism.

In Unitarian Universalism, I found a religious home that shared my revulsion for war, but still welcomed those who felt that sometimes war is necessary to defend freedom and democracy. Unitarian Universalism welcomed the lifelong learner in me who taught religious education classes and wrote curricula for other churches to use. While writing one of my curricula, Thinking the Web, I explored the theory of Just War. Just War is a doctrine of ethics asserting that a conflict can and ought to meet the criteria of philosophical, religious, or political justice, provided it follows certain conditions. An example of these conditions would be “Just cause,” which states that the reason for going to war needs to be just, such as recapturing things taken or punishing people who have done wrong. Another example is the condition of “Proportionality,” which states that the force used must be proportional to the wrong endured, and to the possible good that may come. The more disproportional the number of collateral civilian deaths, the more suspect will be the sincerity of a belligerent nation’s claim to justness of a war it fights.

Taken in it’s entirety, the conditions defining Just War made a good deal of sense to me. At the same time, however, I also wrote a class session on conscientious objection and began to explore the philosophy of pacifism. Honestly, I found unconditional pacifism untenable. I admired Gandhi’s vision of nonviolent resistance, but frankly felt that the position taken by the historic peace churches – the Quakers, the Church of the Brethren, and the Mennonites – simply avoided the challenges we face in a modern global society.

When I entered the seminary, I took a class on Unitarian Universalist History. I wrote a paper on the Unitarian response to Nazi Germany. My research revealed much division in the 1930’s on the issue of pacifism. Those advocating absolute pacifism, led by John Haynes Holmes of the Community Church in New York City, were challenged by ministers such as James Luther Adams, who had traveled in Nazi Germany and foresaw the horrors to come. Many Unitarians straddled the fence, eventually supporting the effort once the European conflict erupted, and more strongly after Pearl Harbor. I found myself sympathetic to what I called Realistic Pacifists, who abhored war, but recognized the necessity of the practice.

And yet, throughout this journey, my doubts grew. I lived through the Gulf War and then the invasion of Iraq. I saw Just War theory brutalized by those with financial motivations, or historic biases against the Muslim people. I read more history, now revealing even more complicity by the United States in the birth and growth of Nazism in Germany and the hatred of America by the Japanese. I began to see more clearly the attitude of Gandhi and Jesus, that violence only propagates more violence, continuing the cycle of humans harming one another.

Which brings back me to my latest landmark on this particular road. One day, I entered the room of a patient. We only shared 30 minutes or so together. Somehow, at that moment, this man decided to share with me his experiences in Vietnam. I believe in synchronicity – that sometimes two events or two people can come together in some larger meaning, but that there need not be any identifiable cause for the meeting. What this man had been feeling for 40 years came flowing out with me.

During CPE, students spend time in clinical sites, in small group processing exercises, and in more traditional learning sessions called didactics. Just the day before, my group learned about Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) during a didactic. This man exhibited every symptom.

- He had been exposed to traumatic events during the war;

- He reexperienced these events over the years in flashbacks and nightmares;

- He had never been able to talk about things even related to the experience that would trigger these memories;

- He experienced persistent difficulty with sleep, anger, and being hypervigilant, that is, sensitive to things such as loud noises; and

- He had experienced these symptoms for years and they significantly impaired his ability to function in social and work settings.

As we spoke, I shared my feelings about my brother and stories Jon had shared with me. He told his own stories, including one about a Vietnamese girl who used to come into the soldiers’ PX. He said that the soldiers bought her whatever she wanted because she was so pretty and innocent. He went on to tell me that, one day, he picked her up…and she exploded. She had been booby-trapped.

He began to cry and I joined him. He was frustrated by his tears, but I told him what I had learned the day before. You have been through a traumatic experience. Crying is the reaction any normal person should have when faced with such an abnormal experience. These tears have waited 40 years to come out of you.

Afterwards, I reflected on this visit and felt deep sadness for this man. I could only imagine the tragedy of his life for the past 40 years. I realized fully for the first time that the victims of war include not only the dead, the wounded, the imprisoned, and the displaced, but all of the soldiers engaged in the conflict, their families and friends, and everyone whose lives they touch. I realized that no cause, no reasons, no justification could warrant the destruction of war, the destruction that war caused this man for the past 40 years. And, I knew that we will continue to devastate the lives of men like this until we end war; until we disavow all violence toward one another; until we pledge once and for all not to harm each other.

Therefore, I have committed to live the rest of my life nonviolently. I will militantly defend the innocent with my own life if needed. But, I will strive never again to harm another person mentally, physically, or emotionally. I make the distinction set forth by John Haynes Holmes in his 1916 book New Wars for Old, in that I will lift my “militancy from the plane of the physical, to the plane of moral and spiritual force.” As a human being, I will struggle to maintain this pledge. As a human being, I recognize that I will harm others. But, as a human being, I know that we have the potential to end war; we have the potential to love each other; we have the duty to try to live nonviolently. The cycle of people harming one another cannot stop until enough of us pledge to end our violent behaviors.

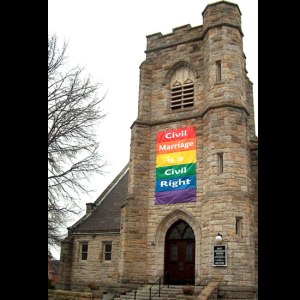

Will I advocate that the Unitarian Universalist Association join with the Quakers, the Church of the Brethren, and the Mennonites, and become a peace church? Yes. But, I will also advocate that we understand that the path to pledging to nonviolence can be long and difficult. I will advocate patience and understanding as people struggle with the commitment. As a noncreedal peace church, Unitarian Universalism can become a home for people struggling to make this commitment where they will not be judged for their current position on the matter; a home for further discussion about both the practical and the theoretical issues of war and peace; and a home for people to share their feelings and experiences openly in loving community.

(this is the bulk of the text of a sermon I delived on Sunday, August 10, 2008 at the First Unitarian Church of Pittsburgh)